Internment

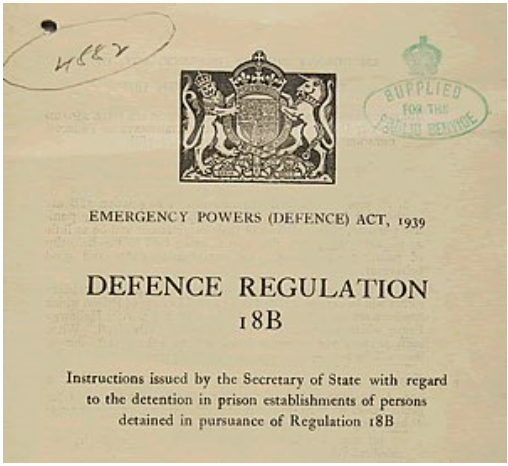

Regulation 18B

The dark Years

Alfonso Pacitti

Many young and older men living in the UK of German and Austrian heritage were arrested under the infamous Government Order 18B shortly after the start of WWII in 1939. When Italy entered the war on the side of Germany on 10th June 1940, the internment activity was extended to include Italian families and sympathisers.

So within a few day, most Italian males aged between 17 and 60 living in the UK had been interned as ‘enemy aliens’ under Churchill’s famous policy of ‘Collar the lot!’

Before the outbreak of WWII, the War Office had worked out a plan to take care of enemy aliens, should war break out. It grouped them into categories based on rank and position. The first group known as Category 'A' was allocated to officers and gentlemen who could afford to pay their mess bills while the second category 'B' was for other ranks. This system failed because of the sheer numbers of aliens involved and had to be replaced with another based on an assessment of risk to the State.

After war broke out, it was decided that all German and Austrians, male or female, should appear before their local Enemy Alien Tribunal and be classified into three new categories:

- 'A'- Doubtful risk, posing a potential threat — to be interned at once

- 'B' - Loyalty a little suspect — remain at liberty

- 'C' - No risk

The rapid advance of the German army through Europe and into Northern France to occupy the Channel Ports accelerated the threat of invasion of the United Kingdom. As a result, mass internment began in earnest from 15th May 1940. At first it was just German men between the ages 16 to 60 but with the Italian entry into the war on 10th June 1940, Winston Churchill instructed the Home Secretary, Sir John Anderson to intern all adult male Italians as well, together with anyone, even British citizens, deemed to have ‘sympathies’ towards the enemy.

For the initial months there were no Alien Tribunals, there was no right of appeal, there was no real categorisation; everyone became a category ‘A’ alien (even UK citizens) and there was no communication with families left behind. A number of men were arrested under this order even though they did not fit any of the defined requirements for internment. It took nearly a year before most of those who were really ‘B’ and ‘C’ category internees were released. In July 2010, some remarkable original documents were put on show at the National Archives Scotland offices in Edinburgh. They also shed some additional light on events surrounding the sinking of the SS Arandora Star, some 70 years previously.

The loss of the ship carrying hundreds of interned Italians to Canada was a very heavy blow to the Italian community in Scotland. It was already reeling from the riots and looting which erupted across Scotland when Italy declared war on Britain on 10th June.

When the Arandora Star was torpedoed off Ireland by a German U-boat on 2nd July 1940, among those who died were 446 Italian internees. Ninety-four came from Scotland and four of those who perished were Pacitti men. The exhibition used previously unseen Scottish Office and other official records to tell the story of some of the Scots-Italians caught up in the tragic events of 1940.

A Saughton Prison register lists some of the Scots-born Italians who were interned and initially held in Edinburgh. Among them was Eduardo Paolozzi (1924-2005), who was later released because he was too young. He lost his father and grandfather on the Arandora Star, but he went on to become an artist, and achieved international fame as a sculptor and print-maker. Below the entry for Paolozzi in the extract below is another Pacitti, Andrea from Edinburgh. Official files reveal the personal and material losses of the Scots-Italians. They include the tragic case of Antonio Mancini from Ayr, an immigrant who had become a British subject. He was wrongfully detained and lost his life on the Arandora Star, so the Government agreed to compensate his widow; one of the very few cases where any form of compensation has been made.

Official files reveal the personal and material losses of the Scots-Italians. They include the tragic case of Antonio Mancini from Ayr, an immigrant who had become a British subject. He was wrongfully detained and lost his life on the Arandora Star, so the Government agreed to compensate his widow; one of the very few cases where any form of compensation has been made.

Alberto Pompa, whose café on Leith Walk, Edinburgh was wrecked, raised a court case. It failed because of a legal technicality, but fortunately the Scottish judges later upheld his appeal in an important judgement.

Since the government had rounded up too many internees for them to hold safely in the UK, agreement had been reached with Canada and Australia for them to house a number of the prisoners. One young lad, Antonio Da Prato, was sent to Canada. Antonio (Toni) was the nephew of Rosa Bertolini, my grandmother, who lost her husband Silvio on the Arandora Star. Toni sent the following postcard in July 1943 to his ‘Zia’ to let her know that he was ok.

Toni is standing at the back, furthermost left. On the reverse of the postcard he wrote:

Back to Top"“Cara Zia, Ecovi la promessa fotografia, state bene come sto io, e saluti a tutti. Vostro nipote Toni”

“Dear Auntie, here is the photograph that I promised, keep well as I am too, best wishes to everyone. Your nephew Toni”