Cover Up

Alfonso Pacitti

December 2021

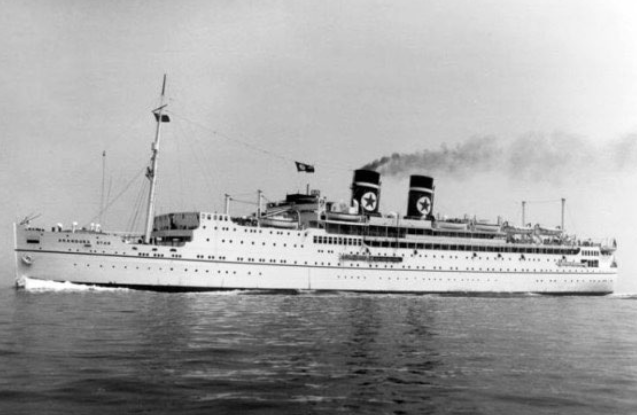

“If it were to sink, we shall be drowned like rats”

protested Captain Moulton before the Arandora Star set sail; prophetic words indeed.

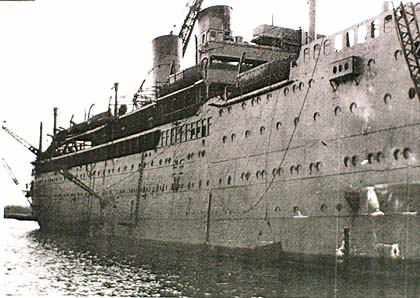

The lid has been kept very tightly shut by the UK Government on the Arandora Star tragedy. Initially subject to the usual wartime 30 and 50 year embargoes, much of the relevant material was subsequently and inexplicably extended to 85 years. Is there something to hide? This was one of the largest maritime losses suffered by the United Kingdom in WWII. Only the sinking of HMS Hood (1415 lost) and HMS Glorious (1218 lost) claimed more victims than the Arandora Star. And yet there has been minimal official communication on the loss. There has been some material and information uncovered on the matter, mostly from US sources; which ironically permit access to the same material that the British Government keeps hidden from its own citizens.

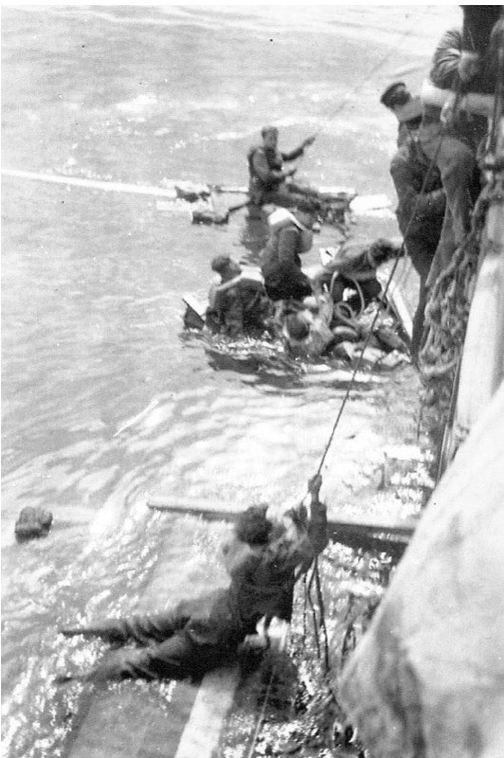

When Intelligence Office Captain C. M. C. Lee made it to the deck, he found the Military Officer in command of the ship, Major Christopher Bethell, of the Royal Tank Regiment, and Captain Goddard already there. Lee asked Bethell for instructions, but Bethell gave none. The ship was listing and Captain Lee departed to search for spare lifebelts and, as he put it gently “was occupied in controlling internees.” In fact, as one survivor put it, “indescribable chaos‟ now reigned on board.

Below decks the ship’s lights had failed, mirrors were shattered and ruptured pipes spewed out noxious fumes. Those rushing to the deck found their escape barred by the barbed wire that the guards had secured in place to keep the internees below decks. Internee Ludwig Baruch heard recalled “panic, muffled cries, an urgent, wailing alarm and hurried steps along the corridor.” Leading cabin mates along a corridor Baruch found a soldier with bayonet fixed to his rifle still on guard. Like his superior officers, the soldier was shocked and confused and, though the ship was sinking, he would not leave his post and ignore his orders.

British official opinion blamed the high loss of life in the sinking on fighting onboard and panic and cowardice amongst the internees as Arandora Star began to sink. A report to the Admiralty sent soon after the sinking explained that: ‘Aliens had appeared on the upper deck and greatly hampered the crew in the launching of the lifeboats.’ The London Times carried the headline ‘Germans and Italians fight for lifeboats – Ship’s officers on bridge to end.’ The propaganda value of portraying the brave British against the cowardly enemy was clear. But a later Admiralty report referred to the lack of panic on deck, instead castigating the internees for refusing to jump overboard, a point surviving internees also made.

Parliamentary questions soon brought to light some of the real story. The conditions the internees were kept in had contributed to the high death toll. Italians, mostly older men, on the lower decks were unable to make their way to the deck. The Germans and Austrians on the upper decks had a much higher survival rate. Bodies, for example, had been found with a lifebelt on. However the lifebelts on the boat were to be worn only after the wearer was in the water. If a person jumped into the sea wearing the lifebelt, the force of the water would push it upwards, breaking the wearer’s neck. Many of the prisoners were unable to swim and would probably have been terrified at the prospect of jumping into the cold ocean in the dark.

Lieutenant J. F. Constable was the only surviving officer of the Ship’s Guard. Constable was responsible for internal security onboard the Arandora Star, and he kept in close contact with Captain Moulton. He commented that he:

Nine months after the event, in March 1941, Constable wrote a personal and confidential letter to the War Office. It made unpleasant reading for the authorities investigating the sinking of Arandora Star. He started his letter with the following chilling comment:'saw things and obtained information that no other Officer, either casualty OR survivor had access to."

'“Do you wish me to give you a complete recital of the stark facts which will enable you to give absolute reasons why the percentage of military casualties was 39 percent, a statement which would make informative but unpleasant reading, or do you wish me to ‘soft pedal’ the whole affair?”

Whitewash

The sinking of Arandora Star was the subject of a private inquiry by Lord Snell. Lieutenant Constable, who knew that the military and internees had no instruction in emergency drill, was the only surviving officer who was not asked to submit a report on the sinking to Snell’s inquiry.Snell’s report was completed in October 1940 and only a Cabinet summary is available; the full report has never been published. The report was a whitewash which absolved the war cabinet from any responsibility and hid the muddle and ineptitude surrounding Britain’s internment and deportation policies in 1939 and 1940. In the rush to intern those who ‘might constitute a grave danger to security’, many harmless individuals were picked up. The Arandora Star was intended to carry only known Fascists and Nazis, but selection was at best random. There were many cases of mistaken identity when the prisoners were originally interned. Many of those who died should never even have been onboard.

The British press and Members of Parliament alleged that: ‘interned aliens who are Nazi sympathisers have been persuading other aliens to impersonate them and be deported to Canada in their names.’ In fact, the errors were due to faulty intelligence from the British security services, but MI5 was unwilling to take any responsibility. The responsibility lay with the prisoner of War Directorate of the War Office, under the responsibility of Anthony Eden, Secretary of State for War. Eden had been distinctly unhappy about Snell’s inquiry, but had been compelled to change his mind by Churchill.

Snell reported that he saw ‘no reason to question the decision that those who were deported should have been deported.’ No one would be blamed fully, no heads would roll and all would agree it was a sad result that arose ‘because of the position which then obtained’ in wartime. However, as a result of his findings, British internment policy was relaxed and subsequently deportation overseas was abandoned. On the orders of Cabinet Secretary, Snell’s report was never published.

Later, Constable understood why he was not called to give evidence:

Other sources suggest a deliberate loss of memory amongst the military. Intelligence Officer, Captain F. J. Robertson, told the War Office that he regretted:“After a Parliamentary enquiry and report, a full statement of facts might be misunderstood; therefore, as a good soldier, having kept it ‘under my hat’ for nine months, I can, if necessary, continue to do so, giving you only a ‘useful’ but innocuous story.”

Ludwig Baruch, in a similar vein to Lieutenant Constable, wrote more openly:“that at the present moment I can give you no very precise information regarding the fate of the Officers and men missing from the SS Arandora Star. I have even forgotten the name of the Officer who commanded the escort company.”

“the sights I witnessed were not fit for human eyes to see.”