Arandora Star

The Fateful Voyage

Alfonso Pacitti

updated December 2022

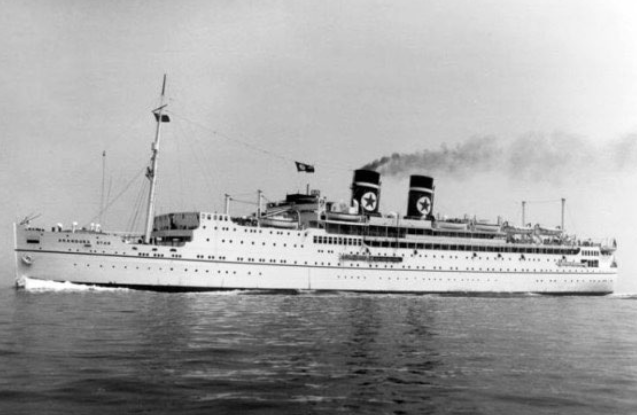

The Arandora Star was built by Cammell Laird & Company Ltd at their Birkenhead shipyard and launched in 1927. It was originally designed for the fast passenger and refrigerated cargo services to South America and South Africa.

She was upgraded in 1929 as a luxury cruise liner and her name was changed from the original Arandora to the Arandora Star. Its owners, the Blue Star Line, used it for long pleasure voyages to Norway, Northern Capitals, the Mediterranean and the West Indies. As a luxury cruising liner, it normally carried around 350 exclusively first-class passengers. Edgar Wallace Moulton, from Liverpool, had been appointed Captain of the liner since the early 1930s. With her white hull and scarlet ribbon she sometimes went by the name of the ‘chocolate box’ or ‘wedding cake’.

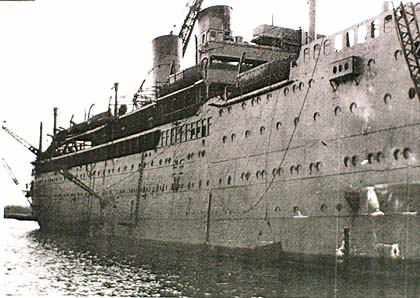

At the onset of World War II, the Arandora Star was repainted dull grey and dark blue and put into service for the armed forces as a transport ship. Ironically, at the start of 1940, she had been fitted with experimental anti-torpedo net. Although the tests had been successful, the nets were subsequently removed a few months later.

In May 1940, she sailed from the Firth of Clyde to help evacuate troops from Norway. In June, she evacuated more troops from France before undertaking what was to be her final voyage; transporting German, Austrian and Italian nationals who had been interned under 18B regulations and enemy prisoners of war to Canada.

Fully armed, the vessel had been fitted with a 4.7inch cannon against sea attack and a 12 pound anti-aircraft gun.

Shortly before the internees were boarded, barbed-wire barricades were placed on the promenade deck.

At 4am on 1st July 1940, the Arandora Star cast off her moorings and set sail from Liverpool without an escort, still under the command of Edgar Wallace Moulton.

She was bound for St. John's, Newfoundland and Labrador in Canada, and the newly commissioned internment camps there. On board were over 1,150 German, Austrian and Italian internees, including some POWs, being transported from Britain. In addition there were also 436 British men, comprising 254 military guards and 182 crewmen.

The Italians numbered 706 men of all ages. Most of them had been residing in Britain when Mussolini joined Hitler and declared war against the Allies on 10th June. The Italians were also the first large group of prisoners to embark and the majority were accommodated on the ‘A’ deck, the lowest deck. This sad but important fact would contribute to the high number of casualties among the Italians; nearly 65 percent of them were to perish.

The ship was not bearing any Red Cross sign, which could have shown that she was carrying prisoners, and especially civilians. This was contrary to Geneva Convention guidance.

Eighty percent of the crew had been newly signed on that morning. Many of the new crew were from the army rather than the navy and had no ‘maritime’ experience. No emergency drill or instruction was given either to the crew, the military guards or to the internees.

U-boat

Towards midnight the Arandora Star rounded Malin Head, the most northerly point of Ireland, heading westwards. The prisoners were mostly asleep in their cabins. Just after 06:30am, the course of the ship fatefully crossed that of German submarine, U-47. At 06.58 am off the north-west coast of Ireland, she was struck by a torpedo from the submarine, commanded by U-boat ace Günther Prien. Prien and his submarine were responsible for the sinking of over 30 Allied ships in the early part of the war. His most famous attack was the sinking of HMS Royal Oak at anchor in Scapa Flow.

Captain Prien had been observing the Arandora Star via periscope for nearly 30 minutes. His Captain’s Log showed that the ship was travelling at 15 knots, armed fore and aft and was plying a zig-zag course. With its grey wartime livery, visible gun and cannon placements, lack of any other indications and frequent course changes, Captain Prien naturally took the boat to be an armed merchant cruiser. U-47 fired its remaining single damaged torpedo at the Arandora Star. The two vessels were now less than 2500 metres apart and it took just 97 seconds for the torpedo to reach its target. All power on board the stricken boat was lost at once, and thirty-five minutes after the torpedo impact, the Arandora Star sank. Eight hundred and sixty-five lives were lost.

"I could see hundreds of men clinging to the ship. They were like ants and then the ship went up at one end and slid rapidly down, taking the men with her. Many men had broken their necks jumping or diving into the water. Others injured themselves by landing on drifting wreckage and floating debris near the sinking ship" - Sergeant Norman Price

Rescue

At 0705 hours Malin Head radio received the first distress call, which it retransmitted to Land's End and to Portpatrick. A Short Sunderland flying boat was dispatched to locate the vessel and its survivors.

The modified cruise ship carried only fourteen lifeboats, of which one was immediately destroyed upon torpedo impact. Another could not be lowered off its winches, and two were damaged during their launch and thus useless. Other lifeboats were launched too early before men had a chance to evacuate the ship and they drifted away, far from the stricken vessel. At least four of the remaining lifeboats were launched with a very small number of survivors. One other lifeboat was swamped and sank itself shortly after the ship foundered. Captain Otto Burfeind from the SS Adolph Woermann, who had been captured as a German prisoner of war, stayed aboard the sinking ship helping to organise the ship's evacuation until he himself was lost when it finally sank.

The ship carried one thousand passengers over and above her normal capacity with insufficient life-jackets and life-boats for everyone on board. Survivors’ witness accounts describe many of the military guards as simply not trained for an emergency of this scale; which was not surprising. Those who were able to get to the life-boats first had to circumnavigate the fences and barbed wire that separated them from safety. Those who were able to access the few available life-jackets leapt into the water from too great a height, instantly breaking their necks.

As the ship continued to list, the covered mirrors that surrounded the ballroom fell smashing onto the passengers causing more horrific injuries. There were sons who would not abandon their injured fathers. Many of the internees could not swim. As the ship began to list even more, the cannon on the stern broke its mooring dragging down the barbed wire, which in turn dragged down more men clinging onto the ship.

At the time, there was much partisan, xenophobic and inaccurate UK press comment that the large loss of life was in part due to inappropriate actions of the prisoners on board. However, all of the interviews with survivors reported a totally different story of valour and mutual support.

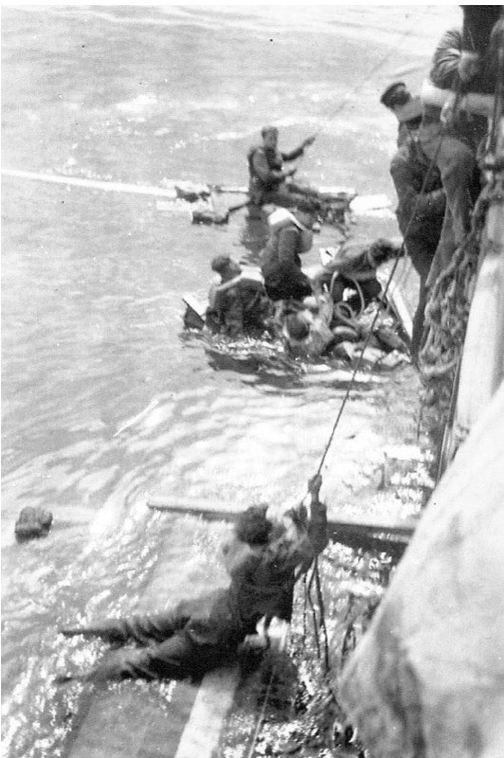

After a brief scout by a Short Sunderland flying boat that was following their SOS distress signal, the Canadian destroyer HMCS St. Laurent (H83) arrived to pick up the survivors. Over 870 men in total were rescued and taken to Greencok, Scotland. Of the 1171 detainees only 583 survived.

Read Captain DeWolf's (HMSC St. Laurent Captain) own memories of the rescue via the link on this page.

The sick who totalled 132, were taken to Mearnskirk Hospital after disembarking. 200 Italians and 251 Germans & Austrians were taken to Birkenhead army camp before being re-embarked on another commandeered cruise ship (SS Dunera) and taken to Australia under the most disgraceful of conditions; which were to raise concern and belated action by both the Australian and British authorities.

The Master of the Arandora Star, Edgar Wallace Moulton, was posthumously awarded the Lloyd's War Medal for Bravery at Sea, and the Canadian Commander, Harry DeWolf, was cited for his heroism in the rescue operation, as was Captain Burfeind.

The stunning rescue photograph at the beginning of this article was taken by crew members aboard the HMCS St. Laurent and is reproduced courtesy of Keyhart Productions Inc. Canada.

It also forms the cover of the excellent book by Maria Serena Balestracci: Arandora Star - Dall’Oblio alla Memoria.

Her book provides a fascinating and harrowing insight into the tragedy.